Cleaning the irrigation ditches, “acequias,” is a tradition in Northern New Mexico. Farmers dig acequias to bring water to their fields. Every spring, at the beginning of the growing season, the community gathers to weed and dredge the ditches, so the water goes where farmers want it to go and waters what they want it to water. Acequias have deep roots and a holy place in Pueblo and Spanish New Mexican culture.

Cleaning the acequias has long been one of my favorite metaphors for Lent. This week, as I was listening for what wanted to be written to you, I realized that cleaning the acequias is a tame metaphor. It doesn’t work for me anymore.

What’s Lent?

Lent shares a root with the word “lengthen” and refers to the seven weeks before Easter, a time of lengthening daylight in the Northern Hemisphere. Lent is when many Christian religious folk prepare intentionally for Easter by taking on a Lenten discipline.

Lenten disciplines often involve giving something up—chocolate, alcohol, social media—or taking something on—Bible study, meditation, decluttering. The point of a Lenten discipline, traditionally, is to make room in one’s heart and life for the risen Jesus on Easter Sunday. A focus on sin—how we fall short—and penitence—how we can punish ourselves so we’ll do better—loom large in this traditional mindset.

Many progressive clergy and church communities do their best to steer their Lenten focus toward spiritual growth and wholeness. Given the deep rootedness of sin and penitence in Lent, they’re fighting an uphill battle.

Back to acequias.

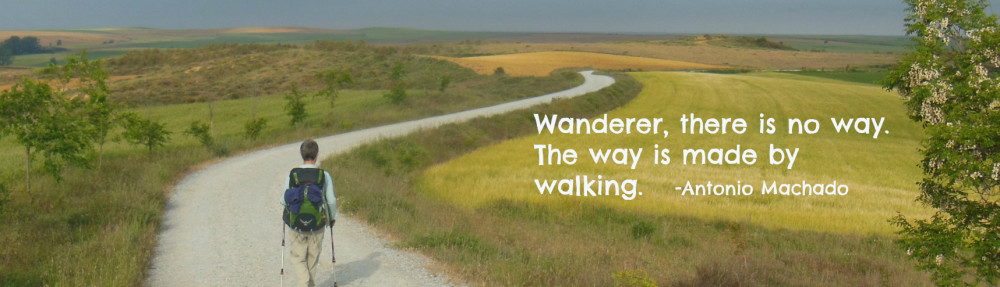

Irrigation, no matter how picturesque or historic, domesticates wild water. Copious, noisy, wild water, flowing downstream from snowy mountains, is diverted into smaller and smaller channels. Weeds are not allowed, only crops that meet the needs of farmers or landowners.

Four years ago, I wrote “A letter from God to her daughters who observe Lent.” It went a little viral in 2019 and has now been read over 60,000 times. I think that post resonates so deeply because those words refresh and renew like cold, clear water. They feel good in our bodies. They feel healing. They feel true. They feel like love.

Traditional religious ideas about sin and penitence can hurt. There is no healing in fear-based disciplines.

“The Cathedral and the Well” is the story of a pilgrim walking through the desert, searching for water. She’s checking old maps and sees that water is around somewhere, but she can’t find it. She’s desperately thirsty, and all she sees is a ruined building made of dry, dusty stones. Then, in the silence of the desert, she hears the faint sound of flowing water. She follows the sound and discovers that it’s coming from the building! She moves a loose stone aside and the sound gets louder. She continues to pull away stones until there’s a gap big enough to crawl through. Once within, she sees a spring of living water emerging from the dirt. She drinks deeply.

For centuries, pilgrims passing this way piled stones to mark the location of the spring. Over time, the stones had completely covered the life-giving water. (I’m renaming this story “The Cathedral and the Spring.”)

We can choose Love-based disciplines. We can choose wild disciplines. This Lent, I want to love the wildness in me. I want to love my internal wilderness—the inappropriate, unkempt, honey-sticky, dirty, weedy, weird parts—the parts I try to hide. The parts I haven’t quite gotten tamed so I keep them closeted and caged.

Peregrina Martha explores wildness through the lens of old-growth trees in this excerpt from Lost & Found, my Camino novel. (For more, you can download a free PDF here. The novel’s a bit of a mess in places, with occasional salty language.)

Going Wild

I watch my hand that holds the hammer that pounds me into a shape that fits the proper hole. I pound and pound myself, but I don’t quite fit. I squeeze a bulge in here, shave off a sharp edge there, and pound and pound and pound. I try to whittle myself down to nothing so I can disappear. Bang bang bang on my head hits the hammer. Square peg in round hole. Redwood into toothpick. I cut the inconvenient pieces off. I limb myself so I slide smoothly into the mill.

Limbs are where the wild things live – where birds make their nests.

Limbs are an impediment to masts and poles. I will wield the ax for you. Let me cut off my limbs to make myself suitable for industry. I will make myself straight and rigid and useful to you powers. Let me read your mind and do what you want before you ask it, so you are blameless.

Behold the limbless handmaid of the Lord.

I will stop pounding myself into a hole that will never ever fit. I will regrow my limbs and branches so wild things have a place to live. I will nourish my roots and reach for the roots of others.

I am no longer espaliered.

I am a Redwood. I am an old Ponderosa…

I am regrowing myself. I am undebecoming.

Deep kindness. Compassionate heart.

Put down the hammer and the axe.

Let go. Free fall. Trust.

Allow yourself to be who you are.

Completely here…

We are not a fiber farm. We are not a monocultured industrial forest. We are old growth. We are many- layered, and we harbor secrets. Sasquatch lives within us. We hold stories upon stories. Our usefulness is not immediately apparent. Tiny communities of uncommon organisms live only in us. We are interwoven and interdependent. We contain entire ecosystems in our crowns. Marbled Murrelets nest in our upper limbs, bathed in Pacific fog. A thousand feet above the ground, seedlings sprout from leaf duff six feet deep.

We are the old ones. The living ones…

You are deeply loved.

Growing is your job.

Be who you are.

Exform your Self into the world.

Prepare.

Good questions for Lent:

Old-growth Redwoods contain entire ecosystems on their branches and in their crowns. What chopped-off limbs will you regrow? How wild will you let your crown get? What axe will you put down?

Living Water flows in the Wild places. Who’s thirsty in your heart? What desiccated places within you yearn for wild water? What parts of you long to be rewilded? What stones will you dislodge so Living Water flows freely? What internal wilderness will you explore?

These are, for me, good questions for a healing, holy Lent. I offer them to you with love.

P.S. If you’d like my latest writing, news, and coaching offerings delivered to your inbox, please subscribe to my weekly-ish newsletter here, and thank you!

[Photo: Melissa Askew on Unsplash]