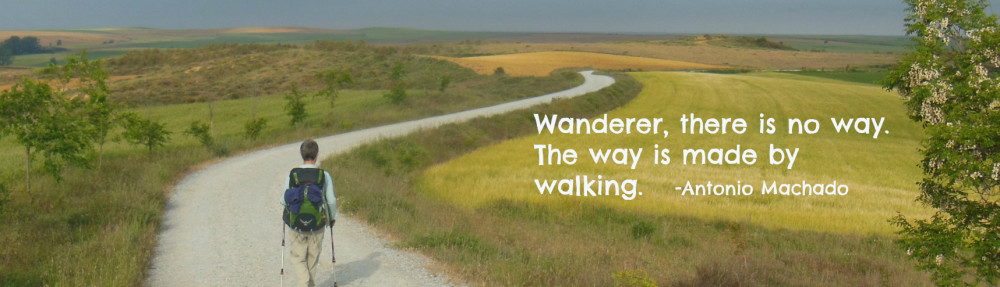

I’ve been steadily writing a novel for over two years – a blink of an eye in novel-writing time. The first scene came in a dream. I crafted my own NaNoWriMo in March of 2017, using the dream scene as a jumping-off point. That writing was “pantsed,” writer-ese for “Screw planning! Let’s just see what happens!” What happened completely took me by surprise. You can read some of it here. Following those crazy days, I introduced planning – crafting a coherent narrative, introducing additional characters, and writing missing scenes. The first draft is almost finished! Here’s the opening chapter of Lost and Found: A Journey on the Camino de Santiago (working title).

Suburban Chicago, Late May

Martha handed in her keys for the last time and went home to empty her closet and dresser. She took all the sensible clothes, the khakis and cardigans and school spirit t-shirts and sturdy shoes, to Goodwill that afternoon. She kept only a few pairs of blue jeans and two t-shirts for gardening.

A bright yellow t-shirt and lime green skirt were hanging in the Goodwill window. They went fabulously with the plastic flamingo pink flip flops in the shoe section. Martha bought them all.

The next day, the books. All gone. She’d left her classroom library and best practice books for the bright shiny teacher taking her place. She fully expected the new teacher to throw the texts away, but held out hope that some kid someday would read Wizard of Earthsea. She took all the self-help and the novels to Goodwill, too.

Two days after her last day as a sixth-grade teacher, Martha walked out the front door of her mostly empty house and climbed into the waiting cab. She carried only a backpack that held two changes of clothes, a few basic toiletries, her Goodwill purchases, and her trekking poles. Inside the backpack was a smaller bag with a paperback book, passport and credit cards, and 300 Euros donated by her former colleagues at her retirement party. She hadn’t wanted a party at all, so it was a small gathering of team teachers and a couple of principals. She was the last of the group that had started teaching together 25 years before.

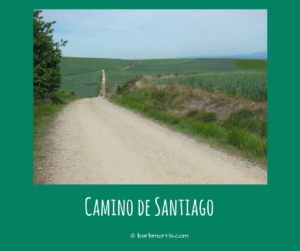

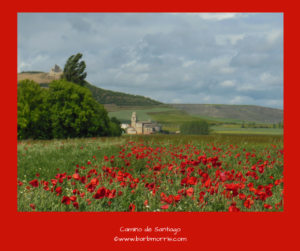

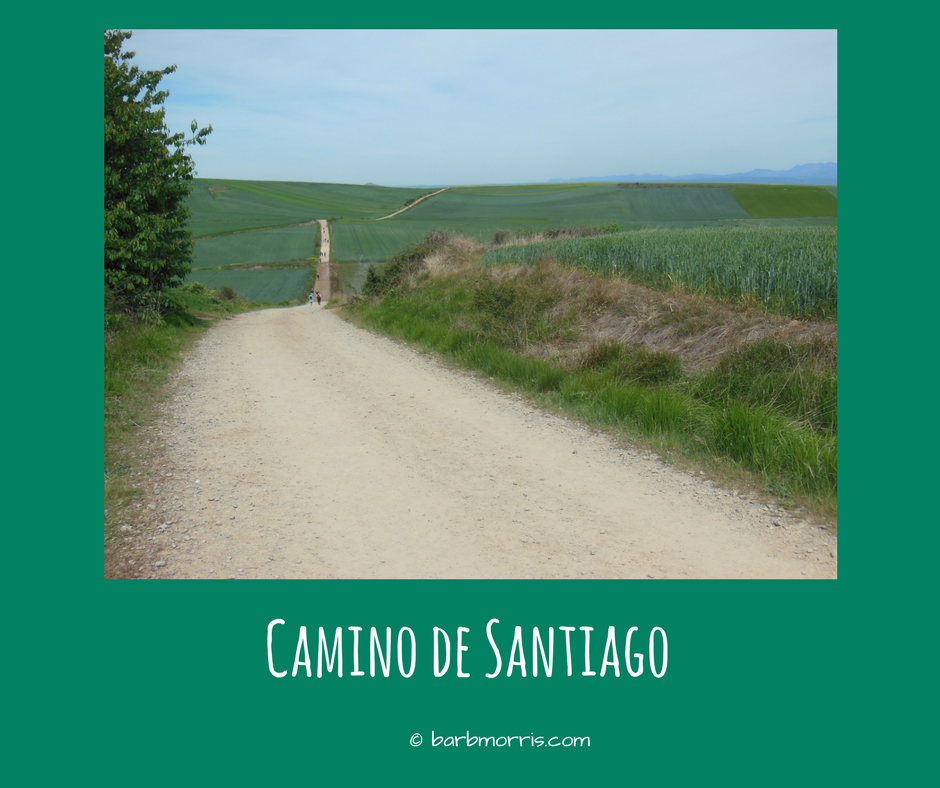

She was flying United to La Guardia, then Iberia to Madrid. From Madrid she’d take a train to León and the bus to Pamplona, where she’d start walking the Camino de Santiago de Compostela.

Santiago de Compostela, the terminus of many Caminos – routes from all over Spain and from a few cities in France. And from Portugal. Even from England, although that route was mostly the ferry from Portsmouth, then three days of walking in Spain.

Martha thought, not for the first time and certainly not for the last, that she was crazy to be doing this. She was 62 years old, healthy but not in perfect physical condition. Her Spanish was rusty. And she was alone.

What better way to mark the end of an era? What better way to tend the ending of her working life and to invite in whatever was next? You see, she didn’t know what came next. When her retirement had become public knowledge, the Camino was a handy answer for the inevitable question at staff meetings and in the teacher’s lounge, a place she usually avoided. Martha had asked her principal not to tell anyone until the new teachers for the coming year had been hired. She didn’t want her retirement to be a distraction for the last couple of months of school. She just wanted to teach – to pay attention to this ending as fully as she could.

The questions. Oh, the questions. “So, Martha, what are you going to do next year when we’re all back in school? Do you have plans? Are you going to get another dog? It’ll be nice to spend more time with your kids, won’t it?”

She’d answer, “Actually, I’m spending the summer in Spain, walking the Camino de Santiago.” She liked the surprised look on their faces. She’d enjoyed surprising someone for a change.

The inevitable follow-up question was, “Who’s going with you?”

“No one,” she’d say. “I’m going by myself.”

“Is that safe?” they’d ask.

“A lot of people do it, so I hope so. It’s fine. Joy is meeting me in León for a few days in the middle to check on me. I’ll email the kids when I have wifi.”

She would see the doubt cross their face and find it mirrored in her own thoughts. What the hell am I doing?

Yet there Martha was, at Chicago O’Hare, checking her backpack, carrying on only a book and the small bag. The ticket agent wished her a good flight as she handed over her boarding passes. She went through security to the waiting area, sat down, and fought the rising panic that had become her constant companion. Fear’s voice with its predictable litany once more took a run through her head: This is a batshit crazy idea. I don’t know why I’m doing this. I don’t have to do this. I could walk right through that door there and catch a cab back home. I could be in my house tidying up and tending the garden. I could start the kitchen remodel. I could paint the study. I could wake up in my own bed. I could get in shape for this. Train for it. Do it next fall when it’s cooler. What the hell am I thinking?

Somehow, she kept her seat. She let the voice yammer on, and sat. She stayed in her seat until her flight was called, when she stood up and walked down the jetway and onto the plane. She found her seat and, once again, she sat. She didn’t speak. She didn’t trust herself to speak. If she talked, she’s not sure she’d ever shut up. I’m alone on this fool’s pilgrimage, she thought. No conversation with strangers will change that. Just for a moment she pondered taking a vow of silence for the duration of this journey. She could hang a sign around her neck that said, “In Silence.” Tempting.

She didn’t get up until the plane landed at La Guardia. Her flight to Madrid didn’t leave for three hours. Three hours. Three hours to change her mind. To come to her senses. Her backpack would go to Spain without her. Then she remembered the empty closet. The empty bookshelves. The almost-empty house. Her empty former life. What had she done?

Her phone rang. Her son.

“Hi, Matt.” So much for the vow of silence.

“I’m fine. I’m sorry I didn’t call. So much to do. You know. Yes, I’m in New York between flights. The Madrid flight will be boarding any minute. You got the itinerary I sent you, right? I’ll check in when I have wifi. Yes, sweetie. I promise. Give Flora a kiss for me. Spain is a first world country, dear. Thank you for taking care of her. I’ll miss you. Not going to back out now, dear. I’ll be fine. I love you. Mwah. Bye.”

Martha silenced her phone and put it away in her bag. She sat, unmoving, until her row was called. She got up and walked to the gate and down the jetway, onto the big plane that flies across oceans. She found her seat, shoved her little bag under the seat in front, buckled her seatbelt, looked out the window, and smiled.

All I have to do is put one foot in front of the other, and walk. Babies do that. I can do that.

She’d had so many ideas about this Camino. So many theories. So many thoughts. Now it was here. She was suddenly aware that she didn’t know anything anymore. She didn’t need to know anything. All she had to do was walk. All she had to do was follow the arrows and walk to Santiago.

But first, she had to get to Pamplona.