THIS IS A SCENE FROM MY CAMINO NOVEL-IN-PROCESS. PLEASE SEE THE FIRST EXCERPT, “THE MESSIES,” WHICH INTRODUCES THE NOVEL AND WHY I’M POSTING THIS WRITING IN ITS RAW STATE.

THIS IS A SCENE FROM MY CAMINO NOVEL-IN-PROCESS. PLEASE SEE THE FIRST EXCERPT, “THE MESSIES,” WHICH INTRODUCES THE NOVEL AND WHY I’M POSTING THIS WRITING IN ITS RAW STATE.

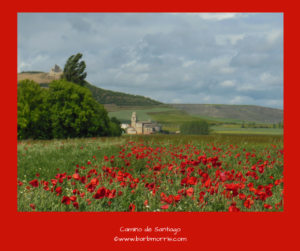

Martha is sitting in a field of poppies with a frozen child in her lap. She notices that although poppies are soporific in stories, on the Camino she hears them say “Wake up!” She croons to the child, strokes her, puts her cheek to the little girl’s cold face, listens to the Meseta wind and watches the poppies sway, for what seems like hours. Softly holding this frozen girl – waiting for signs of life.

She sees peregrinos walking in the distance – they’re far enough away that she can’t tell them apart – occasionally one will notice her and wave. She waves back so they know she’s okay. A woman leaves the road and walks through the poppies toward them. Martha watches the expressions cross the woman’s face as she gets nearer. She sees surprise, concern, comprehension, and finally immense kindness.

“Hola,” she says. “How can I help?” They recognize each other’s American-ness by all the nonverbal cues – North Face and Osprey, smiles and eye contact.

“She’s frozen. I’m thawing her.”

“You must be tired. Let me take a turn.” Martha realizes that, yes, she is indeed tired. The woman takes her towel from her backpack and spreads it on the ground, then sits on it and reaches her arms to Martha. Martha gently hands her the curled up girl child.

The woman asks, “Where did you find her?”

“In my chest,” says Martha.

“Ah,” says the woman, and she looks at Martha with deep brown eyes. “I understand.”

Martha knows those eyes. She’s looking into her mother’s eyes. As their eyes fill with tears, the girl child stirs. Martha reaches out a hand to the girl’s face. It’s warm, and she catches a tear softly falling down the girl’s cheek. Thawing is happening rapidly now – the little girl is breathing and stretching and making little noises as she wakes up – Martha sees that this child is younger than she thought – maybe 4 or 5 – red rubber toed sneakers, little jeans, a pink shirt, fine brown hair cut like a bowl on her head like the Beatles used to have – and deep brown eyes looking up at her and her mom.

“Hello, sweetheart,” says Martha.

This is weird, she thinks. I’m sitting in a field of Spanish poppies with my mom, who’s been dead for twenty years, and a little girl I found in a freezer in my chest. Okay, then. Smiling, she lies down in the sun in the poppies, looks at her mom cradling the smiling child, and closes her eyes. She feels the rocks beneath her and knows she’s getting dirty and damp, and she doesn’t care. It’s totally worth it to feel the Earth along her entire body. Ground below; air and sky above. Poppies all around. She reaches out her hand to the woman sitting next to her, places it on the woman’s nylon-clad leg, and relaxes. As she falls asleep she wonders – will they be here when I wake up?

They are. They are deeper in the poppies, holding hands, the little girl bending to smell each flower and laughing as they sway in the breeze. The sun was halfway between noon and the horizon. Martha is hungry. She sits there watching the two dear creatures, listening to her daughter’s tinkling laughter that sounded like a creek in the summer and her mother’s low murmurs in response.

That’s surprising, she thought. That’s who she is to me. Martha stands up, brushes the dirt off her legs with a swish, and says, “Hey, you two. Let’s go find supper and a bed.”

They turn and start toward her. Her daughter lets go of the older woman’s hand and runs toward Martha. “Mommy! (That settles that, thought Martha.) You’re awake! Grandma and I were looking at the pretty flowers. She says they’re poppies! Let’s go to that town over there!”

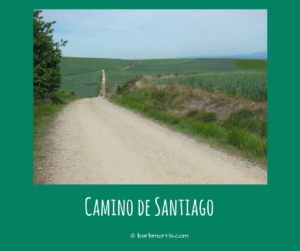

She pointed her little finger toward the town they could see beyond the trees – a large church and monastery at the base of a terraced hill with a ruined castle plopped on top. Who does that? wonders Martha. Who’s designing these quintessential Camino vistas?

She shoulders her backpack and takes her daughter’s hand. Her mom folds up her towel, wipes off Martha’s pants with it to get the last of the dirt, stows it in her backpack and puts it on, straps on her poles, and heads through the poppies back to the road. There are just a few pilgrims still walking as Martha and her girl follow the older woman to the road, holding hands.

Martha understands that her Way just got a lot more complicated. And more companionable.

I don’t know how long I’ll have my mom with me, and my daughter probably isn’t real either, she thought. This is so interesting, and I’ll ride this wave as long as it lasts.

An hour later they walk up the cobbled street through the old gate into Castrojeriz. Martha and her mom have taken turns carrying their little girl, whose name it turns out is Esperanza, almost always called “Hope,” most of the way. As she explained, “I’m tired. After all, I a little girl, and I just woke up after being frozen for a really long time.” Martha suspects she also wanted to feel her mothers’ arms around her, holding her, singing to her, telling her how glad they were that she woke up.

It was like that, that this one, now three, arrived at the door of El Hospital del Alma. And how it is that they are the fortunate pilgrims who find themselves sitting in front of a warm wood stove, drinking chamomile tea with honey, eating cookies and chocolate-covered strawberries off flowered china plates, asking the hospitalera where to stay, and are invited to stay in her one guest room that just happens to be empty that night.

“I will cook for you dinner,” says María, “and you will tell to me your story.”