THIS IS A SCENE FROM MY CAMINO NOVEL-IN-PROCESS. PLEASE SEE THE FIRST EXCERPT, “THE MESSIES,” WHICH INTRODUCES THE NOVEL AND WHY I’M POSTING THIS WRITING IN ITS RAW STATE.

THIS IS A SCENE FROM MY CAMINO NOVEL-IN-PROCESS. PLEASE SEE THE FIRST EXCERPT, “THE MESSIES,” WHICH INTRODUCES THE NOVEL AND WHY I’M POSTING THIS WRITING IN ITS RAW STATE.

The next town is coming closer. Martha doesn’t want to be with people tonight. She wants to sit with this place in her soul. Enter it and not be distracted. Not have to interact. She understands now those peregrinos who have passed her, unspeaking, earbuds in, no eye contact. They were simply finding solitude.

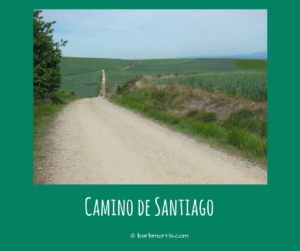

The gravel Camino becomes a cobbled street as Martha enters the town. She looks for an albergue with a bench and flowers out front – it’s her rule to look for flowers. Three doors up on the right – geraniums – Las Aquedas. The door is open. The hospitalero* is seated behind a rickety blue table covered with paper, his guest register open on top of the pile.

“Hola, señor. ¿Tiene una cama?”

He looks up, taking her in kindly. “Sí, señora. Tengo una cama para usted. Bienvenídos. Pasaporte y credential*, por favor.”

Martha shrugs off her backpack and digs out her American passport and pilgrim credential. The hospitalero writes her name, passport number, and nationality in his register. Solemnly he inks his albergue stamp, presses the stamp carefully into her credential, and dates the stamp. In this way, she’ll prove her journey to the volunteers at the pilgrim office in Santiago to receive her compostela* at the end of this ridiculous walk. “¿Cuanto cuesta la cama?,” she belatedly asks.

“Seven euro,” he answers, in English. “If you want breakfast it will be ten.”

“Breakfast, please. Grácias, señor.” She hands him a €10 note, picks up her backpack, and goes to find an unclaimed bed. As late as she is, it’ll almost certainly be a top bunk. Which makes the inevitable peeing in the middle of the night an unwanted adventure, but so far so good. She hasn’t killed herself yet. All the bunks along the walls are claimed, top AND bottom. This albergue, like many others, has crammed more beds in to take advantage of the increased pilgrim traffic since Americans and Koreans have discovered the Camino.

Damn Martin Sheen*, she thinks, not for the last time. And, also, bless him, Lord. That, too. I’m here because of him. And so are all these other people. She spots a bottom bunk smack in the middle of the big room full of bunk beds – almost all with backpacks propped beside them and a few clothes – shirts, pants, socks – strewn on them. Most hospitaleros frown on pilgrims putting backpacks on the beds. She’s not sure why.

Some of the beds have clotheslines strung in front, with towels draped on them for a little privacy. She puts down her backpack, sits on the bed, and carefully takes off her shoes and socks. Then, slowly, she removes the betadine-soaked gauze from Max to see how he’s grown. He’s thriving. Tonight, she thinks, it’s time to try the needle and thread. Enough is enough. Crocs on, she gathers her albergue clothes, towel, washcloth, and Dr. Bronner’s lavender castile soap (the all-purpose Camino cleaner), being careful to remember her ziploc-bagged passport, credential, cash, and credit cards, and goes in search of the showers.

Would these be co-ed?, she wonders. Would the hot water last? Would there even be water pressure? How long will it take her to figure out the controls? Would there be a way to keep her clothes and valuables dry? Would the lights go out mid-shower? Would there be a door, even? There wasn’t, always. So many unknowns, every night. And every night, it seems, she learns another thing she’s taken for granted that is evidently up for grabs in a Spanish albergue.

After the blessedly warm shower, she washes her other pair of underwear, her socks, and her t-shirt. Everything else could wait a few more days. Out comes the all-purpose Dr. Bronner’s lavender castile soap again – lavendar to repel bed bugs, an occasional problem on the Camino. Some peregrinos wash their clothes in the shower, also frowned upon by hospitaleros and other pilgrims.

Supper, as she promised herself, she eats alone.

The next day, as usual, she’s one of the first ones out the albergue door. Even though she paid for breakfast the night before, she’s left at the crack of dawn. Not before the crack of dawn, like some potentially annoying peregrinos who strap on their headlamps when it’s still dark and rustle their belongings into their packs and creep, they think quietly, out the albergue while the stars are still out. She’s not that driven.

But she relishes the half hour or so before sunrise – the brightest stars are still shining, and there are only a few other pilgrims as the sky lightens and she walks through a mostly quiet village – the only sounds the crunch of her shoes, the tap of her poles, early birdsong, and roosters waking up. She loves this time, she’s discovered, when rural Spain smells like wood smoke and sheep shit. She’ll stop for breakfast – toast and café con leche – at the next village. For now, it’s just good to walk. Hospitalero coffee is never as good as the café con leche she’ll get in the bars. And somehow the toast isn’t as good either.

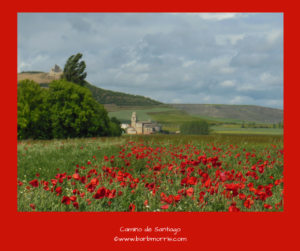

What is it about Spanish toast anyway? Who knew a 60-year-old American woman could walk for miles fueled only by toast?! Surprising – she who spent decades as a carbophobe. She sort of lives for Spanish bread. With jam and lots of butter, at breakfast. And a chocolate croissant for a snack. And tortilla. Ensalada mixta* for second lunch or for dinner, because it’s the only vegetables she’ll get all day. Fresh-squeezed orange juice she’ll discover later.

I want to travel, Martha thought. I want to live in Spain for awhile. I want to really BE here. Maybe a volunteer hospitalera? I promise myself I will not let myself be tethered. I will not let myself be caged. What’s an Airbnb in Madrid in July and August? Or Glasgow? Or Belfast? Or London? Or Galway? It’s so easy to get tied down. No No No.

Her mind panics. How would I support myself? How would I live?

And then there it is. The Voice. Writing and art, Martha. Writing and art, poppy seed. Writing and art and living REALLY cheaply. What do I need, after all? Clothes (a few), a place to sleep, food to eat, a way to keep clean, a way to make a living (computer and art supplies?)… I don’t need so much. I don’t need a car. I don’t need a wardrobe. I’d LIKE a little dirt.

All of this as she walked the first couple of miles of the fifteen she had planned for the day. She already knew it was going to be one of those Camino days full of voices – days that were coming more and more frequently. Shirley McLain’s* got nothin’ on me, she thought.

We make choices that lock us in before we know any better, she saw. We believe the lies about achievement and career and A to B to C in proper order. We believe the lies about rules and earning love through compliance and being useful to others. I just want to be WILD. I just want to be free for a change. That’s what I want. That’s all I want.

And immediately the fear and the doubts creep in. As she walks she can feel them. They’re a constriction around her heart. I’ve never even written so much as a short story, she thinks. And what about helping people? Aren’t I supposed to help people?? I’ve never sold a painting. I’m going to make a LIVING at this?! What the FUCK am I thinking?!

Then below the panic, below the fear, the ground, she heard the Voice say, “Artist.”

You are my artist. You are one of my artists. You are one of my poets and painters and storytellers. You have the heart for this work. You’ve been a teacher. Thank you, my dear. Those kids needed you, and I’m grateful. Now it’s time for something new and deeper and unknown. Teaching was the freest path you could take when you believed the lie that you had to earn MY love and your worth.

I don’t know how to do this, she answered. Also, who ARE you?

You know who I am. The Earth Voice continues. When you feel afraid, it’s because you’re believing something that’s not true – like there’s a right way and a wrong way, you have to look competent, you have to be right, you have to get it right. There is no such thing as right.

Martha thinks: But how will I do this without a plan?

Earth answers: Here’s the plan, dearest: there is no plan. We don’t need no stinkin’ plan. (The Voice is evidently a fan of classic movies.) You show up and create – let out all that stuff inside you – bottled up and wanting to move through you – and that’s the plan.

Martha answers, This is crazy. This is batshit. You know that, right?

Then, after a few minutes of walking, she whispers, Can I really DO this?

What would happen if you didn’t, my love? replied Earth. My strong beautiful artist, I love you so much. You are SO strong. There’s no statute of limitations on creativity, dearest. There’s no statute of limitations on being who you are.

*CAMINO PLACES, NAMES, AND THINGS WHICH WILL NEED TO BE DEFINED, OR PERHAPS I’LL INCLUDE A CAMINO LEXICON.